Copyright National Humanities Center, 2015

What arguments did Bartolome de Las Casas make in favor of more humane treatment of Native Americans as he exposed the atrocities of the Spanish conquistadors in Hispaniola?

Understanding

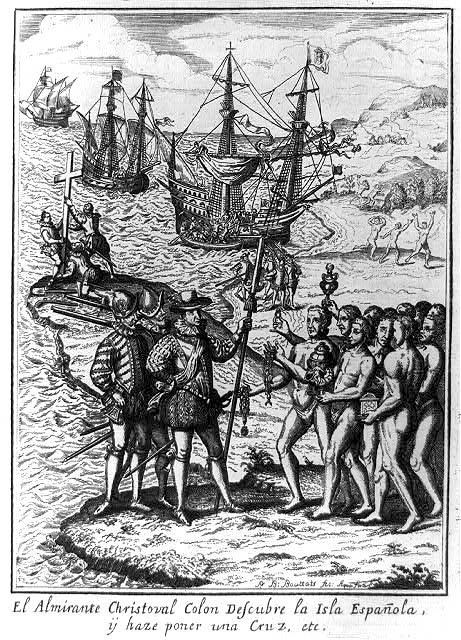

First contact experiences on Hispaniola included brutal interactions between the Spanish and the Native Americans. Conquistadors subjugated populations primarily to garner personal economic wealth, and Natives little understood the nature of the conquest. As early as 1522 Bartolome de Las Casas worked to denounce these activities on political, economic, moral, and religious grounds by chronicling the actions of the conquistadors for the Spanish court.

![Portrait of Bartolome de las Casas]()

Text

Bartolome de Las Casas, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies.

Text Type

Book excerpt, Literary nonfiction.

Text Complexity

Grade 11-CCR complexity band.

For more information on text complexity see these resources from achievethecore.org.

In the Text Analysis section, Tier 2 vocabulary words are defined in pop-ups, and Tier 3 words are explained in brackets.

Click here for standards and skills for this lesson.

X

Common Core State Standards

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.1 (cite evidence to analyze specifically and by inference)

- ELA-LITERACY.RI.11-12.6 (determine author’s point of view)

Advanced Placement US History

- Key Concept 1.2 (IIB) (Spanish colonial economies marshaled Native American labor…)

Teacher’s Note

Using excerpts from A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, published in 1552, students will explore in this lesson how Bartolome de Las Casas (1484–1566) argued for more humane treatment of Native Americans in the Spanish New World colonies. In the first excerpt students will look at the author’s general description of the actions of the Spanish on Hispaniola, home to the Taino Indians. In the next three excerpts students will investigate the Spanish presence in a specific Hispaniola kingdom, Magua. De Las Casas argued to the Spanish King that his agents, the conquistadors, were brutalizing native peoples and that those actions were destroying the Spanish as well as the natives. A Brief Account details extremely graphic interactions between the Taino and the Spanish, but by strategic excerption this lesson works to temper the more sensational descriptions of atrocities while remaining true to the tone of the original text.

This lesson approaches American first contacts by reminding students that the exploration of the Americas involved brutal invasions with economic rather than religious objectives uppermost in the minds of the conquistadors. The New World inhabitants little understood the goals of the invaders and were not able to launch a successful defense.

The events related in this lesson occurred mainly during the reigns of Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452–1516) and Isabella I of Castile (1451–1504). Their marriage in 1469 marked the uniting of Spain through a joint reign, although both Aragon and Castile maintained independent political, economic and social identities. De Las Casas occasionally refers to the Spanish as “Castilian.”

This lesson is divided into two parts, both accessible below. In addition to close reading questions, interactive exercises and an optional followup lesson accompany the text. The teacher’s guide includes a background note, the text analysis with responses to the close reading questions, access to the interactive exercises, and the follow-up assignment. The student’s version, an interactive PDF, contains all of the above except the responses to the close reading questions and the follow-up assignment.

Teacher’s Guide (continues below)

- Background note

- Text analysis and close reading questions with answer key

- Interactive exercises

- Follow-up assignment

|

|

Student Version (click to open)

- Interactive PDF

- Background note

- Text analysis and close reading questions

- Interactive exercises

|

Background

Background Questions

- What kind of text are we dealing with?

- When was it written?

- Who wrote it?

- For what audience was it intended?

- For what purpose was it written?

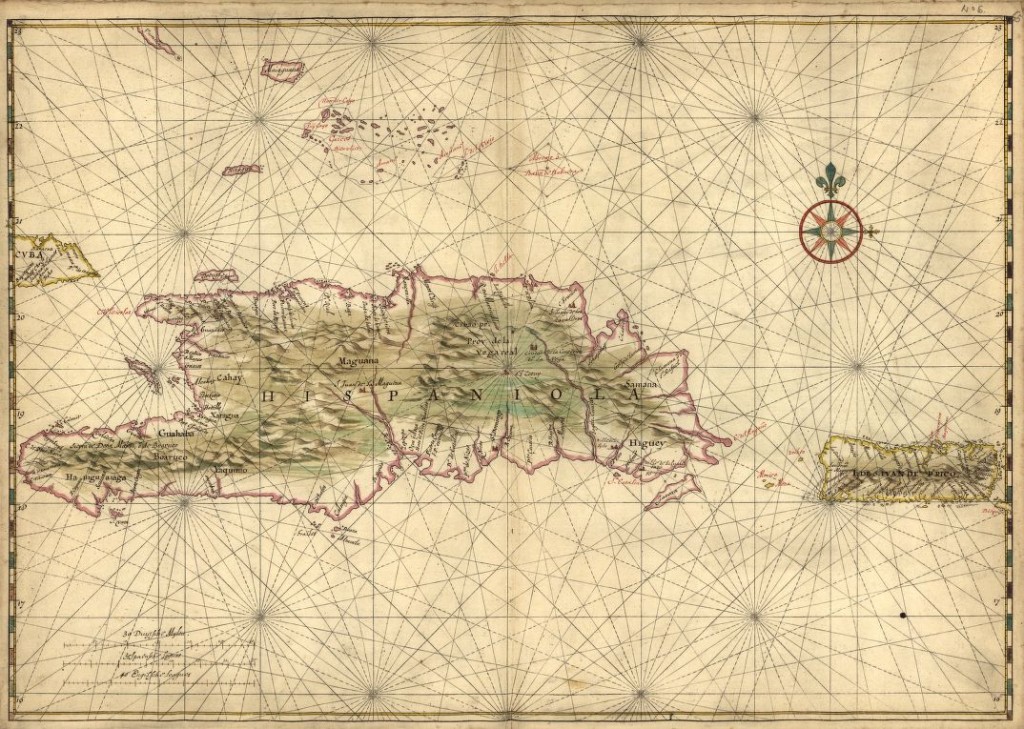

In this lesson you will explore excerpts from one of the first written accounts of interactions between Spanish conquistadors and Native Americans. The first passage describes Hispaniola, the Caribbean island that today includes Haiti and the Dominican Republic. One of the islands explored during his first voyage in 1492, Columbus found there the self-sufficient Taino tribe, numbering up to 3 million people by some estimates. The following passages detail interactions between Spanish conquistadors and the Taino.

Why did the Spanish land in Hispaniola? In brief, they explored for “God, Gold, and Glory.” King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, known as the “Catholic Monarchs,” sought to centralize Spain as a Catholic stronghold. Religious passions spread widely after Spain had driven Moors and Jews out of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, and the Pope issued a decree in 1493 exhorting Spain to spread the Catholic faith into new lands. In addition, Pope Alexander VI granted to Spain any new world territory not already claimed by a Christian prince, and these newly discovered lands offered wide opportunities to convert to Christianity large numbers of “heathens.”

In order to understand the Spanish hunger for gold in the 16th century, one must recognize the Spanish treasure fleet system. Spain at this time had a strong navy but no real industry within the country, and so she had to buy all her goods from other nations, making gold and silver very important. To help fund their naval and colonial activities in the midst of competition with Portugal, the Spanish King and Queen financed Columbus’s voyages to search for trade routes and fresh sources of gold and silver through new colonies. The New World gold and silver mines became the largest source of precious metals in the world, and Spain passed laws that colonists could trade only with Spanish ships in order to keep the gold and silver flowing through Spain. The large flow of treasure to Spain from the capture of the Aztecs (1517), the Incas (1534), and Mexico (1545) sharpened the appetite for gold and silver in Hispaniola.

Columbus was soon followed by other explorers seeking glory for themselves as well as for Spain, including Bartolome de Las Casas (1484–1566), author of this text. Las Casas knew Christopher Columbus — his father and brother went with Columbus on his second voyage, and Bartolome edited Columbus’s travel journals. The Spanish King awarded de Las Casas and his family an encomienda, a plantation that included the slave labor of the Indians who lived on it, but after witnessing the brutality of other Spanish explorers to the local tribes, Bartolome gave it up. He became a Dominican priest, spending the rest of his life writing, speaking and encouraging the Christian conversion of the North American natives by peaceful rather than military means. De Las Casas started a mission in Guatemala and wrote several accounts, aimed at the king and queen and members of the royal court, that sought to expose the brutal methods of the conquistadors and persuade Spanish officials to protect the Indians. The excerpts in this lesson are from probably the best known of those accounts, A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies, published in 1552.

What were the effects of his work? While the Pope had granted Spain sovereignty over the New World, de Las Casas argued that the property rights and rights to their own labor still belonged to the native peoples. Natives were subjects of the Spanish crown, and to treat them as less than human violated the laws of God, nature, and Spain. He told King Ferdinand that in 1515 scores of natives were being slaughtered by avaricious conquistadors without having been converted. He sought to protect the souls of Spain and the conquistadors against divine retribution for the destruction of the native populations by awakening the moral indignation of Christian men to counter the growing tide of barbarism. Between 1513 and 1543 Spain issued several laws attempting to regulate the encomienda system and protect native populations, but enforcement was haphazard and the subjugation of the native populations was already a fact. Nonetheless, through his self-proclaimed goal of bearing witness to the savagery of the Europeans against the simply civility of the indigenous peoples, de Las Casas became characterized as the conscience of Spanish exploration.

If the immediate impact of his work was marginal, the long-term influence would be substantial. In the passages excerpted here and throughout A Brief Account, de Las Casas repeatedly asserts that he witnessed the events he is describing and thus bases his argument on the authority of his first-hand testimony. This practice makes his work an early example of empiricism, the idea that arguments and conclusions should be based upon observable fact. Unquestioned today, in the 1500s this was a new concept, for at that time people held that the proof of an argument should be based on the interpretation of texts rather than the concrete experience of an eye witness.

De Las Casas’ book describes events he witnessed on the island of Hispaniola. As your read these excerpts think about what the Indian kingdoms were like when the Spanish arrived. How did the Indians initially respond to the Spanish? How did the Spanish respond to the Indians? How does the fact that de Las Casas was an eyewitness to these events lend authority to this account?

Text Analysis

Excerpt 1

Close Reading Questions

1. What did the Spanish do to the Natives?

They enslaved them and took their food.

2. How would you characterize the Spanish treatment of the natives?

It was very violent. The author describes the capture as “bloody slaughter and destruction.”

3. How did the Natives come to characterize the Spanish? Why?

The Natives came to believe that the Spanish “had not their Mission from Heaven” because the Spanish so cruelly treated the Indians. The Indians saw them as evil.

4. What does this characterization tell us about the original perception of the Natives regarding the Spanish?

They originally perceived them to be from heaven and believed that they had come for positive purposes.

5. How did the Natives respond to the Spanish cruelty?

They hid their food from the Spanish and hid their wives and children in “lurking holes” [caves]. Some of them ran away to the mountains to escape punishment by the Spanish.

6. How did the Natives respond to the Spanish violence against them? What were the results?

The Indians “immediately took up Arms.” However, the author describes the native weapons as those that boys play with rather than real weapons. They had very little effect.

7. Once the Spaniards realized that the Indians were resisting, what did they do?

The Spaniards mounted their horses and attacked cities and towns, killing everyone.

8. What tone does de Las Casas create in this excerpt? How does he create that tone? Cite evidence from the text.

De Las Casas uses diction (word choice) to create a tone of outrage. He is angry at the injustices being done to the Natives. He uses phrases such as “the bloody slaughter and destruction of men,” “making them slaves, and ill-treating them,” “laid violent hands on the Governours,” and “exercise the bloody butcheries.” De Las Casas conveys immediate physical violence through words like “bloody,” “destruction,” “violent,” and “butcheries.” He conveys short and long-term violence, including the losses of liberty and culture, through words like “slaves” and “ill-treating.”

9. How does de Las Casas portray the natives in this passage? Cite evidence from the text.

He portrays them as naïve, innocent children. It apparently took them a while to figure out that the Spanish were not on a “Mission from Heaven.” The Indians are essentially defenseless against the Spanish, and when they do take up arms, their weapons resemble those of boys.

10. How does this portrayal advance de Las Casas’s argument?

It establishes the vulnerability of the Indians and illustrates why they need the protection of the Spanish king.

In this excerpt de Las Casas speaks of the beginning of Spanish atrocities on the island of Hispaniola. Pay attention to how the Spaniards viewed the inhabitants of Hispaniola, to how the Natives originally viewed the Spanish, and to how the Natives’ perceptions changed.

(1) In this Isle, which, as we have said, the Spaniards first attempted, the bloody slaughter and destruction of Men first began: for they violently forced away Women and Children to make them Slaves, and ill-treated them, consuming and wasting their Food, which they had purchased with great sweat, toil, and yet remained dissatisfied too,… (2) and one individual Spaniard consumed more Victuals in one day, than would serve to maintain Three Families a Month, every one consisting of Ten Persons. (3) Now being oppressed by such evil usage, and afflicted with such greate Torments and violent Entertainment [treatment] they began to understand that such Men as those had not their Mission from Heaven; and therefore some of them conceal’d their Provisions and others to their Wives and Children in lurking holes, but some, to avoid the obdurate and dreadful temper of such a Nation, sought their Refuge on the craggy tops of Mountains; for the Spaniards did not only entertain them with Cuffs, Blows, and wicked Cudgelling, but laid violent hands also on the [Taino] Governours of Cities… (4) From which time they began to consider by what wayes and means they might expel the Spaniards out of their Countrey, and immediately took up Arms. (5) But, good God, what Arms, do you imagine? Namely such, both Offensive and Defensive, as resemble Reeds wherewith Boys sport with one another, more than Manly Arms and Weapons.

(6) Which the Spaniards no sooner perceived, but they, mounted on generous Steeds, well weapon’d with Lances and Swords, begin to exercise their bloody Butcheries and Strategems, and overrunning their Cities and Towns, spar’d no Age, or Sex….

![map of Hispaniola]()

Map of the islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, 1639

Excerpt 2

Close Reading Questions

11. How many kingdoms were located on the island of Hispaniola?

Six kingdoms composed the island.

12. Describe the Kingdom of Magua. What does its name mean? How large is it in square miles?

Magua was the name, which means “campaign” or “open country.” The island was 80 miles long and an average of 9 miles wide, so the total approximate size in square miles was 720 square miles.

13. In what ways does de Las Casas compare Magua with Europe? What is the effect of the comparison?

He states that the kingdom includes high mountains and a number of rivers, including some very large ones which were comparable to those in Europe. By comparing these to specific European waterways he is emphasizing their beauty and transportation value.

14. In this description, what would be the most important detail for the Spanish King and Queen? Why?

They would be most interested in the presence of gold, since it could strengthen their treasury if sent back to Spain.

15. What is the effect of de Las Casas providing such a detailed geographic description of the kingdom in this excerpt?

By fully describing the environment the reader understands the geography of Hispaniola. By comparing the rivers with ones in Europe the reader understands the scale of the kingdom’s waterways. The reader can imagine the beauty of the kingdom as a paradise. This contrasts the violence in the previous excerpt and sets up another contrast to the violence in the excerpt that follows.

16. In excerpt 1 de Las Casas speaks of Hispaniola overall. In this excerpt he speaks of Magua, a specific kingdom on Hispaniola. What is the effect of shifting his eye witness account from the overall island to a specific kingdom on the island?

The first excerpt explains the overall violence on the island. This excerpt describes a specific kingdom in detail. By describing in detail a kingdom where the violence was located, the violence becomes more personal and less abstract.

In this excerpt de Las Casas describes one of the kingdoms of Hispaniola, Magua, and gives eye witness descriptions of the kingdom’s geography. Why would he go into such detail? How does this paradisiacal description contrast with the violence of excerpt 1?

(7) This Isle of Hispaniola was made up of Six of their greatest Kingdoms, and as many most Puissant Kings, to whose Empire almost all the other Lords, whose Number was infinite, did pay their Allegiance. (8) One of these Kingdoms was called Magua, signifying a Campaign or open Country; which is very observable, if any place in the Universe deserves taking notice of, and memorable for the pleasantness of its Situation; (9) for it is extended from South to North Eighty Miles, in breadth Five, Eight, and in some parts Ten Miles in length; and is on all sides inclosed with the highest Mountains; above Thirty Thousand Rivers, and Rivulets water her Coasts, Twelve of which prodigious Number do not yield in all in magnitude to those famous Rivers, the Eber, Duer, and Guadalquivir*; (10) and all those Rivers which have their Source or Spring from the Mountains lying Westerly, the number [of rivers] whereof is Twenty Thousand are very rich in Mines of Gold; on which Mountain lies the Province of rich Mines, whence the exquisite Gold of Twenty Four Caracts* weight, takes denomination [is identified there].

Notes: Guadalquivir is the second longest river in Spain. Duero is the third longest river in the Iberian peninsula. Ebre is the second longest river in the Iberian peninsula. Twenty Four Caracts (karat) gold is pure gold, containing no other elements.

Excerpt 3

Close Reading Questions

17. Describe Guarionex’s kingdom, including its political structure. Why does de Las Casas describe it as he does?

Guarionex was the “King and Lord” of Magua. The organization of this kingdom is detailed in a very similar way to the medieval kingdoms of Europe, in which vassals and Lords serve the King and, when asked, provide him with an army. In Magua each vassal could contribution 16,000 soldiers. This description would be one with which the Spanish court could identify.

18. De Las Casas describes King Guarionex as courageous, even tempered, obedient, and moral. What is the effect of this description?

It clearly contrasts King Guarionex with the Spanish conquistadors, who are presented as evil. It reminds the Spanish King and Queen that the conquistadors are brutalizing people who not only would be good Spanish citizens but who are also “moral,” that is to say, virtuous people with souls, worthy of conversion and capable of salvation.

19. What relationship did King Guarionex have with Spain? How did he prove this relationship?

He was “devoted to the service of the Castilian Kings.” He had each of his lords present him with a bell full of gold to give to the Spanish.

20. Why was the king unable to continue the full measure of gold tribute?

His men were not talented miners and so he cut the amount of gold offered in half.

21. Rather than large gold tributes, what alternative for making money did King Guarionex (the Caiu) offer in sentence 16?

He offered his loyalty (“service”) to the king of Spain on the condition that he (Guarionex) be allowed to cultivate lands on which the Spanish originally settled. This would allow for farming and food production.

22. According to de Las Casas, even at a reduced tribute how much gold could the Spanish King expect to receive each year?

At least 3 million Spanish crowns per year.

23. If the Taino subjects “understood not the practical use of digging in Golden Mines,” what does that imply about the value of gold in the Taino culture?

It implies that gold was not that valuable to them, or they would have known how to mine it.

De Las Casas describes the relationship between the Taino and the Spanish. What was that relationship? From this account, how did the Taino value gold?

(11) The King and Lord of this Kingdom was named Guarionex, who governed within the Compass of his Dominions so many Vassals and Potent Lords, that every one of them was able to bring into the Field Sixteen Thousand Soldiers for the service of Guarionex their Supream Lord and Soverain, when summoned thereunto. (12) Some of which I was acquainted with. (13) This was a most Obedient Prince, endued with great Courage and Morality, naturally of a Pacifick Temper, and most devoted to the service of the Castilian* Kings. (14) This King commanded and ordered his Subjects, that every one of those Lords under his Jurisdiction, should present him with a Bell full of Gold; (15) but in succeeding times, being unable to perform it, they were commanded to cut it in two, and fill one part therewith, for the Inhabitants of this Isle were altogether inexperienced, and unskilful in Mine-works, and the digging Gold out of them. (16) This Caiu [Guarionex] proferred his Service to the King of Castile, on this Condition, that he [Guarinoex] would take care, that those Lands should be cultivated and manur’d, wherein, during the reign of Isabella, Queen of Castile, the Spaniards first set footing and fixed their Residence, extending in length even to Santo Domingo, the space of Fifty Miles. (17) For he declar’d (nor was it a Fallacie, but an absolute Truth,) that his Subjects understood not the practical use of digging in Golden Mines. (18) To which promises he had readily and voluntarily condescended, to my own certain knowledge, and so by this means, the King would have received the Annual Revenue of Three Millions of Spanish Crowns, and upward, there being at that very time in that Island Fifty Cities more ample and spacious than Sevil it self in Spain.

Note: Castilian – Spanish Castile, even though technically united with Aragon in 1469, retained a separate political identity until 1516.

Excerpt 4

Close Reading Questions

24. How did the Spanish react when King Guarionex reduced the gold tribute?

One of the Spanish captains raped Guarionex’s wife.

25. Based on the Spanish reaction, what can you infer about how they view Guarionex, a king? Why?

They do not consider him a king and do not respect him. They believe he cannot fight back. They would never do something like this to a European king.

26. How did King Guarionex respond to the Spanish?

Rather than attacking in revenge he escaped the Spanish and fled to the Province De Los Ciquayos, where one of his Vassals ruled.

27. How did the Spanish respond to King Guarionex’s actions?

They raised war against the king, “laid waste and desolate[d] the whole region,” and took the King prisoner. They chained him and loaded him on a ship to send him to Spain.

28. What happened to the ship? How did de Las Casas see this as divine (God-given) justice?

The ship was sunk at sea, with a loss of many Spaniards and much gold. De Las Cases saw this as divine justice because he believed God intervened and punished the Spanish because they were guilty of taking Taino gold and imprisoning their King.

29. The Spanish kings considered themselves champions of Christendom during this time, with a special responsibility to spread the Gospel and remain in God’s graces. What is the implication of sentence 24, “Thus it pleased God to revenge their enormous impieties?”

By using the ship sinking as an example of God-given justice, the implication is that if the Spanish king does not protect the natives, like the conquistadors he will also be exposed to God’s wrath.

30. According to de Las Casas what was the true motivation of the Spanish explorers?

The Spanish explorers were motivated by “avarice and ambition.” They wanted to control the Indians and take the Taino lands, including the gold, for themselves.

31. If you were a king or queen of Spain who sent the conquistadors to the New World to Christianize natives and ship back gold and silver to Spain, how would you respond to the story detailed here by de Las Casas? Why?

It would be enraging. It is obviously treason. De Las Casas clearly states that the Spanish explorers were determined to “no more or less intentionally, than by all these indirect wayes to disappoint and expel the Kings of Castile out of those Dominions and Territories, that they themselves having usurped the Supreme and Regal Empire.” The conquistadors were trying to cheat the King and Queen out of the lands, goods, gold and others items to be found in Hispaniola and instead take it for themselves. Their actions imperiled Spain’s role as Protector of the Faith and infringed upon the role of the Spanish king as sovereign to the indigenous Americans.

In this excerpt, the Spanish violently respond to the Taino attempt to reduce the gold tribute. De Las Casas relates God-given justice to the atrocities of the Spanish, and reveals the true motivations of the conquistadors.

(19) But what returns by way of Remuneration and Reward did they make this so Clement and Benign Monarch, can you imagine, no other but this? (20) They put the greatest Indignity upon him imaginable in the person of his Consort who was violated by a Spanish Captain altogether unworthy of the Name of Christian. (21) He might indeed probably expect to meet with a convenient time and opportunity of revenging this Ingominy so unjuriously thrown upon him by preparing Military Forces to attaque him, but he rather chose to abscond in the Province De los Ciquayos (wherein a Puissant Vassal and subject of his Ruled) devested of his Estate and Kingdom, and there live and dye an exile. (22) But the Spaniards receiving certain information, that he had absented himself, connived no longer at his Concealment but raised War against him, who had received them with so great humanity and kindness, and having first laid waste and desolate the whole Region, at last found, and took him Prisoner, who being bound in Fetters was convey’d on board of a ship in order to his transfretation [transportation] to Castile, as a Captive: (23) but the Vessel perished in the Voyage, wherewith many Spaniards were also lost, as well as a great weight of Gold, among which there was a prodigious Ingot of Gold, resembling a large Loaf of Bread, weighing 3600 Crowns; (24) Thus it pleased God to revenge their enormous impieties.

…. (25) The Spaniards first set Sail to America, not for the Honour of God, or as Persons moved and merited thereunto by servent Zeal to the True Faith, nor to promote the Salvation of their Neighbours, nor to serve the King, as they falsely boast and pretend to do, but in truth, only stimulated and goaded on by insatiable Avarice and Ambition, that they might for ever Domineer, Command, and Tyrannize over the West-Indians, whose Kingdoms they hoped to divide and distribute among themselves. (26) Which to deal candidly in no more or less intentionally, than by all these indirect wayes to disappoint and expel the Kings of Castile out of those Dominions and Territories, that they themselves having usurped the Supreme and Regal Empire, might first challenge it as their Right, and then possess and enjoy it.

Follow-Up Assignment

People in positions of power or influence will sometimes change negative behaviors if these behaviors are made public. De Las Casas hoped that by making the actions of the conquistadors well-known he could bring pressure upon them to change their treatment of the Natives. Choose an example from history or current events where this principle has been applied, either successfully or unsuccessfully. You might investigate Helen Hunt Jackson (Century of Dishonor), Martin Luther King, Jr. (Montgomery Bus Boycott or other protests), the Arab Spring (2010–2012), issues from local, state, or national politics, or other topics as directed by your teacher.

In what ways did making an action or actions known to the public change the situation? What were the effects of these changes (or lack of changes)? Once you have finished your research, design a PowerPoint slide, a Prezi, an Animoto, or other technological presentation as directed by your teacher that displays your research. Share your information with your classmates.

Vocabulary Pop-Ups

- victuals: food

- afflicted: causing suffering

- obdurate: stubborn, inflexible

- dreadful: causing fear

- cudgelling: beating

- strategems: deceitful plans

- puissant: powerful

- rivulets: small streams

- prodigious: large

- compass: proper limits

- vassals: subordinate land holders

- potent: mighty; powerful

- endued: endowed

- pacifick: peaceful, calm

- proferred: offered

- condescended: submitted

- remuneration: pay, reward

- clement: merciful; pleasant

- benign: gracious, kind

- consort: spouse of a king or queen

- ingominy: public disgrace

- unjuriously: harmfully, offensively

- abscond: leave quickly and secretly

- devested: taken from

- connived: overlooked

- desolate: destroyed

- fetters: chains, shackles

- ingot: gold or silver brick

- impieties: lack of reverence

- goaded: encouraged

- insatiable: cannot be satisfied

- avarice: extreme greed

- candidly: truthfully

- usurped: overthrown

Text:

- de Las Casas, Bartolome. A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies Or, a faithful NARRATIVE OF THE Horrid and Unexampled Massacres, Butcheries, and all manner of Cruelties, that Hell and Malice could invent, committed by the Popish Spanish Party on the inhabitants of West-India, TOGETHER With the Devastations of several Kingdoms in America by Fire and Sword, for the space of Forty and Two Years, from the time of its first Discovery by them. Project Gutenberg, 2007. [http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/20321/pg20321.html]

Images:

- “Fray Bartholomew de Las Casas,” from the portrait drawn and engraved by Enguidanos. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/23466/23466-h/23466-h.html#fig1 [accessed March, 2015]

- Joan Vinckeboons, “Map of the islands of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico,” c. 1639. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. http://www.loc.gov/item/2003623402/ [accessed March, 2015]

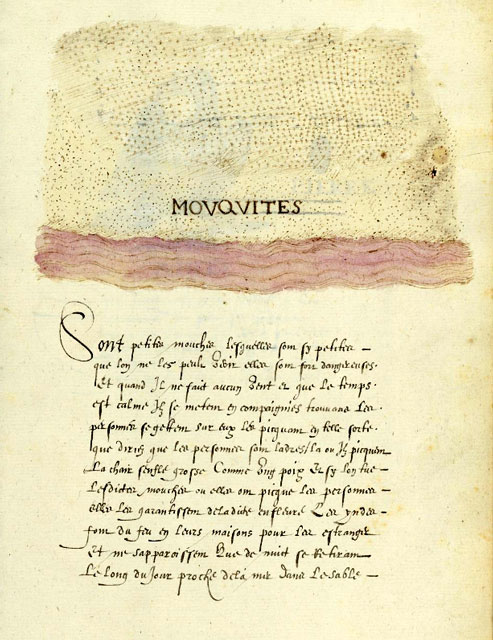

- Histoire Naturelle des Indes, Illustrated manuscript. ca. 1586. Bequest of Clara S. Peck, 1983 MA 3900 (fol. 11v–12) The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. http://www.themorgan.org/collection/Histoire-Naturelle-des-Indes/98 [accessed March, 2015]

The post De Las Casas and the Conquistadors appeared first on America in Class.

![]() on an Inuit man British explorer Martin Frobisher brought to England after one of his voyages to find the Northwest Passage. (Click here for note.) Have students then evaluate how Dodding’s attitudes might have shaped his dealings with native peoples if he ever were to become a colonist. Address the following questions:

on an Inuit man British explorer Martin Frobisher brought to England after one of his voyages to find the Northwest Passage. (Click here for note.) Have students then evaluate how Dodding’s attitudes might have shaped his dealings with native peoples if he ever were to become a colonist. Address the following questions: